The Earth Keeps Track: Pottery, Preservation, and Planetary Precarity

Pottery is precarious work. Historically performed primarily by women, and more recently by self-employed artisans trying to scrape by, ceramics is a craft which requires an inordinate amount of care. A single slip of an untrimmed fingernail can permanently scar an otherwise perfect vessel; a tiny bubble of air surviving the vigorous wedging process can explode under the immense heat of the kiln, scattering shards that shatter nearby pots. For a medium so often consumed with symmetry, simplicity, and purity, there is something inherently and endearingly ephemeral about ceramics. These fragile objects lead lives that are brief and beautiful.

It is, in part, this earthiness, this tactility, that draws people to ceramics. For those of us who spend our days hunched behind desks, staring numbly at tidy fonts as they spread across our screens, an immersion into the improvisational chaos of clay can be invigorating, liberating. It is no wonder that so many people picked up ceramics during lockdown. After a parade of endless Zoom meetings, doom-scrolling, and FaceTime calls accentuating the visceral absence of touch, the process of making pottery can feel grounding in the most physical sense. Leaning over the spinning wheel, steadying your elbows against your knees, feeling the cool solidity of clay gliding between your fingertips, you can trust that you are producing something tangible, purposeful, real. Something you can hold in your hands.

As a ceramicist myself, I naturally gravitated towards the many cases of pottery on display at the Pitt Rivers Museum when looking for objects in the collection which spoke to the themes of the TAKING CARE Project: matters of care in times of planetary precarity.

Pottery is perhaps the most Promethean art form,

representing the mythical subsumption of Nature by Human creativity, the birth

of the artisanal classes and civilisation as we know it. Enter any anthropological

or archaeological museum and you will find ceramic objects; earthenware and

early tools are perhaps the most ubiquitous signifiers of early human

activity. However, rather than cleaving

the two apart, the ceramic arts emphasise the inextricable relationship between

human culture and the natural world.

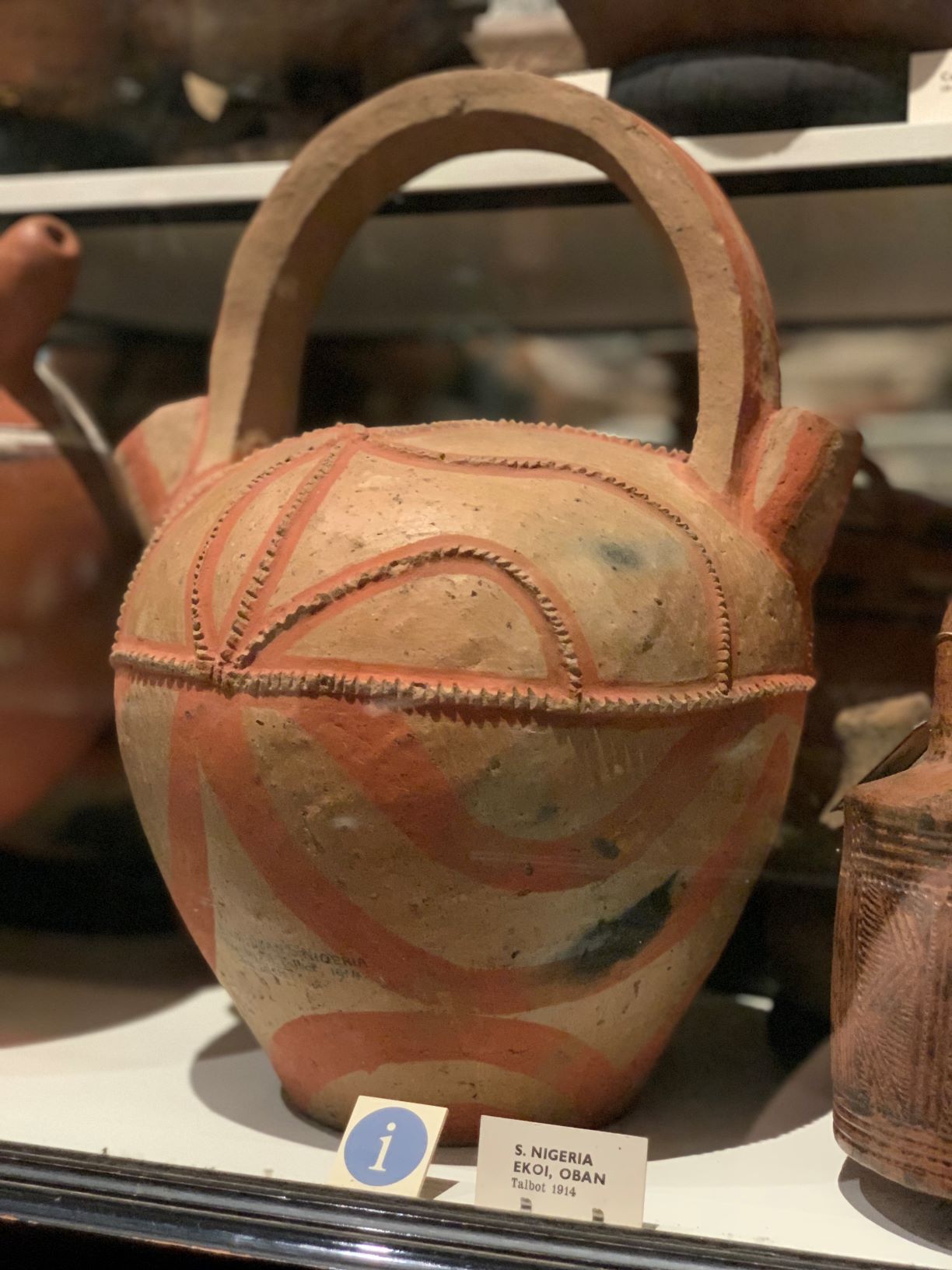

Much of our decorative art and everyday objects are, in fact, simulacra of nature, continuations of the long correspondence between humans, their environment, and the other living beings they share it with. In the cases of the Pitt Rivers, you will find pots whose shapes are suggested by the smooth curvature of gourds; Hopi, Nupe, and Mohica pots rich with animal imagery; Peruvian whistling pots modelled on figures of birds who 'sing' from spouts in their open mouths. While large-scale geoengineering projects like carbon capture and nuclear fusion excite the cultural imagination as ‘solutions’ to human-induced climate change, we might forget that pottery was one of the first ‘nature-based solutions’. The earthenware pots of Nigeria, for example, represent an early climate adaptation through the clever use of evaporative technology: liquids stored within their porous bodies naturally percolate through their outer walls and evaporate, cooling the contents of the pot and making it the ideal vessel for storing liquid in hot and arid regions. Elsewhere, several ancient Egyptian pots were moulded quickly and dried by the sun, designed for brief use before their inevitable disintegration, when the ashes of one vessel might be used to fashion another.

In some ways, it is a marvel that we can still see such objects on display in the Pitt Rivers. Characterised by (and often fetishised for) their fragility, ceramic objects require immense care to preserve them. The question that museums have long needed to ask, and are recently beginning to reckon with, is how do we care for the people who made these pots, largely women, many of whom led lives as precarious and improvisational as their creations?

The earth keeps track. Far from passive, plastic matter, this planet is intimately affected by human activity, as evidenced by ocean acidification, global biodiversity loss, the rapid and unprecedented proliferation of carbon in our atmosphere. Clay, too, bears cultural memory: traces of the fingertips, textiles, and histories of the people who crafted it. Holding a pot in your hand, you can feel the presence of the person who created it, press your fingers into the same grooves theirs once made, before they were robbed of these and other artefacts. Legacies of colonialism are not just figurative; they are inscribed in the raw material of ceramic objects.

Ever since Subhadra Das’ keynote talk for the Matters of Care Conference, I’ve been thinking about her question, ‘What is a museum for?’ The museum presents itself as a site for ‘taking care’: preserving objects, knowledge, history. But often, museums weaponise the concept of care to position only some people as capable of caring for some objects. Das reminded us that museums still serve as visual repositories of the material violences wreaked by colonialism, racism, and imperialism, reifying objects as fetishes while eliding what those objects really represent: people. Having worked in museums before, I know firsthand how easy it is to feel ground down by the machinery of vast, unflinching institutions. But like Das, I remain hopeful: while oppressive structures certainly exist within our institutions, we as individuals have the choice to either uphold or actively try to dismantle them. What is a museum for? Ultimately, the answer is up to us. According to Das, we might begin by listening, acknowledging, and assiduously redressing the injustices which continue to be perpetuated through museum collections. As she so cogently phrased it, 'our inability to talk about race is keeping us racist’.

The Pitt Rivers’ collection of pottery is conspicuously located next to a cabinet labelled ‘Treatment of Dead Enemies’. Now empty and wrapped with informational texts explaining why, the case once held tsantsa, or shrunken heads, recently removed by the museum in response to the dismay Shuar people expressed in seeing their culture represented in ways that perpetuated racist stereotypes. Directly opposite stands my favourite of the museum’s pottery displays, showcasing the continuity of ceramic methods across time, space, and cultures. In one corner sits a small vase and teacup, unobtrusive yet breathtaking, their smooth surfaces punctuated by thin, snaking arteries of gold. These pieces are examples of Kintsugi, the Japanese art wherein ceramic vessels are intentionally broken and then mended using urushi lacquer and powdered gold (kin = gold, tsugi = connect). Beyond their simple beauty, the resulting pieces serve as a powerful parable of ruin and repair, embracing and emphasising their impurities and imperfections.

Much recent work in anthropology has proposed that there is an art to living on a damaged planet, that crafting a better future requires us to reconcile our problematic pasts. The juxtaposition of the kintsugi pottery with the empty tsantsa display struck me as an immensely poignant reminder that the things we preserve, the stories we tell about ourselves and others, and the values our institutions uphold and perpetuate continue to have real and material impacts on the world we share. Museums like the Pitt Rivers have a responsibility to acknowledge the colonial histories of their collections, to render those fractures in bright gold, and to remind us of who and what we are, even and especially those parts of our world system that remain deeply broken. Instead of removing the tsantsa entirely, the case is left to stand, encouraging visitors to reflect upon and reckon with its absence, to question whether it should have been exhibited in the first place.

Crafting a ceramic object is an act of correspondence, building upon the materials and methods of the past, putting them in conversation with the peoples who came before, and with those who might come after. Who knows - if we find a way to sustain life on this planet, future archaeologists might stumble upon our lockdown creations and use them to tell stories about life in 2020. Arundhati Roy recently argued that the pandemic is a portal, offering us the opportunity to break with the past and reinvent a better world in common. Perhaps, the museum too can be a portal, capable of elucidating not only where we come from, but who we might become. Though imperfect and incomplete solutions, the removal of the shrunken heads and the convening of the Matters of Care Conference represent attempts to crack the seemingly impenetrable facade of museum culture - to paint it gold, render it explicit, and, hopefully, build it back better.

Buck, H. (2019) After geoengineering: Climate tragedy, repair, and restoration. London: Verso.

IPCC (2016) Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 ºC.

Kemske, B. (2021) Kintsugi: the poetic mend. London.

Roy, A. (2020) ‘The pandemic is a portal’. Financial Times, p.1.

Tsing, A.L. et al., eds. (2017) Arts of living on a damaged planet: ghosts of the anthropocene. Minneapolis.

Yanagi, M. & Brase, M. (2018). The beauty of everyday things. UK.