As part of the second panel New models for the City with the workshop the ecological sustainability of the city, organised by the Museu Etnològic i de Cultures del Món in Barcelona in November, Carme Trilla (President of the Metropolitan Housing Observatory and the Habitat3 Foundation) talked to us about Social sustainability in European cities in the 21st century.

Social sustainability is inversely proportional to social inequalities. The more the latter grow, the more the former diminishes and vice versa. Housing is one of the main causes of increased social inequalities and, therefore, worsening social sustainability, yet, it could actually be one way to combat such inequalities. So it poses a big challenge and, at the same time, it is a magnificent working tool for improving community life and citizen cohesion in the future.

We can distinguish three aspects in housing inequalities: economic-social, generational and territorial.

The unequal distribution of property wealth and rise in rents well above the income of households most in need under this housing-tenure system – precisely the ones concentrated in the lowest income deciles – are explained in the first of the vectors: economic-social inequalities. According to Andreu Mas Collell, “Increased demand for living or working space comes with a city’s prosperity. That consequently raises the value of this space. It is a structural, that is, underlying fact... Such an increase in value implies that the collectivity is becoming wealthier. But, how is this wealth distributed?... the gains will mainly go to the owners of dwellings... the effect on rent, present or potential, may be overwhelmingly negative. In other words they will not only be denied a share in the new value created, but they will also lose out in absolute terms (because of the rise in rent).” (article entitled “Habitatge públic: com a Viena”, Ara, 28 May 2017)

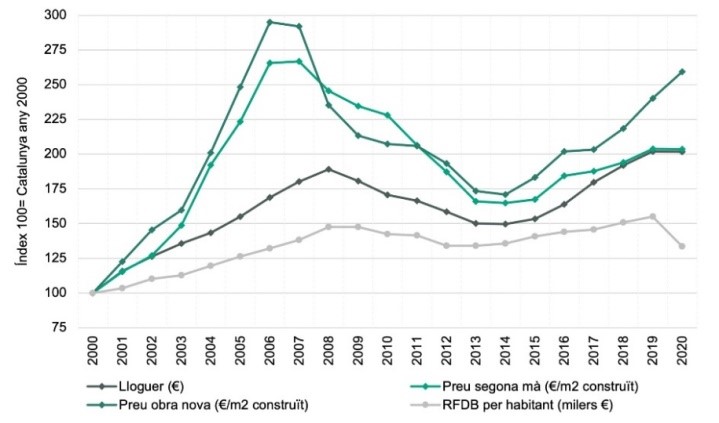

Trend in housing prices and disposable household income in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area. 2000-2020

Some 43% of renting households in Catalonia today have to allocate more than 40% of their income to housing payments, whereas the European average is 27% and the impact of housing on family budgets grew by more than 10 points between 2006 (25%) and 2020 (35.64%).

The generational inequality gap, for its part, can be seen in several age brackets. In the increase in number of children in vulnerable households (35% of children attended to by Càritas Barcelona, compared to an average of 16% of the entire population). Among non-emancipated young people or those who have emancipated late, resulting in a 16.3% rate of emancipation between the ages of 18 and 29, one of the lowest in Europe, having fallen by more than 16 points, compared to the 32.6% seen in 2006. And in households between the ages of 30 and 55 that have suffered the crisis and which, besides suffering the drama of losing their dwelling or the distressing risk of losing it now, face a future of severe residential vulnerability when they reach retirement age.

The last vector of inequality is the regional one. The poor quality of housing stocks, whether because of the extremely poor original construction or because of the age and poor maintenance of the buildings, is one of the wounds through which the virus of inequality passes. Urban planning is a double-edged tool. It can help to sketch very cohesive, integrated and mixed cities or, on the contrary, to feed the processes of exclusion in determining special areas for diverse social strata, generating spacial compartmentalisation and segregation. We all know of cities designed in an exemplary way that have become benchmarks for cohesion, as that aim was implicit in their planning. The democratic aim reflected in integrating urban development plans facilitates cohesion and living in solidarity. By contrast, we also know of cities where the express aim has been to keep the various population groups away from each other, separated on the basis of their economic situation, origins or social class. These cities are not based on solidarity and they are unaware that this divide, apart from being morally reprehensible, constitutes one of the most important risks of destabilisation, conflict and social unrest.

The property structure of cities and their housing systems largely determine their capacity for preventing or mitigating social inequalities. The housing-tenure system, the impact that the public and non-profit sectors have on housing supply, compared to that of the free market, the tradition of public intervention in housing provision, and the public budget allocated to housing policies explain the different response capacity of municipal policies to the housing problems of their respective populations and the diverse combination of these vectors result in cities with more or less success in their goal of social cohesion.

Looking to the future, the principles of urban solidarity will need to inspire proposals for reducing residential inequalities. And this means taking action in four areas: 1) Acting on the built city, renovating buildings and dwellings; creating new affordable dwellings within the existing fabric; public sector and non-profit organisations purchasing buildings and dwellings in order to allocate them to social rental housing. 2) Balancing household incomes with direct financial aid for housing payments. 3) Arranging housing rents with the private sector for households unable to meet market prices. 4) Creating legal conditions for giving maximum residential security to renting households.

A better future is possible if there is a consensus on these issues and long-term agreements are established which focus properly on the goals to be achieved, which are none other than reducing inequalities and gaining social harmony.

Carme Trilla is the President of the Metropolitan Housing Observatory and President of Habitat3 Foundation.