Blog post by Kanika Gupta, TAKING CARE activist in residence at Slovene

Ethnographic Museum

The Slovene

missionaries who came to Kolkata in the early 20th century collected

affordable visual imagery from the markets of the city, which according to them

suitably represented the native religious and visual culture.

Among the

diverse prints and objects that caught their attention are some terracotta and

wooden dolls made in certain villages in India, which are now with the Slovene

Ethnographic museum in Ljubljana. One of these villages was Ghurni,

Krishnanagar in Bengal where the tradition of making clay dolls continues to

this day but has undergone considerable change with time and changing patronage

patterns. This however, is definitely not the only community cluster with the

craft of doll making in India.

Be it made of clay or wood, the large expanse of the world of Indian dolls is simply overwhelming. Jhabua in Madhya Pradesh, Channapatna in Karnataka or Ghurni in Bengal are just a few of the centers of this diverse living tradition.

While

Ghurni is known across the world for its naturalistic clay dolls, the museum

has a set from the same craft cluster some made in wood and some in clay. These

dolls represent Indian people from the village engrossed in different tasks in

their everyday lives and Indian occupations that fascinated the colonizer’s

mind. A typical example is that of the snake charmer, made in clay, luring the

snake out of its basket. The cult of snake worship is deep-rooted in India

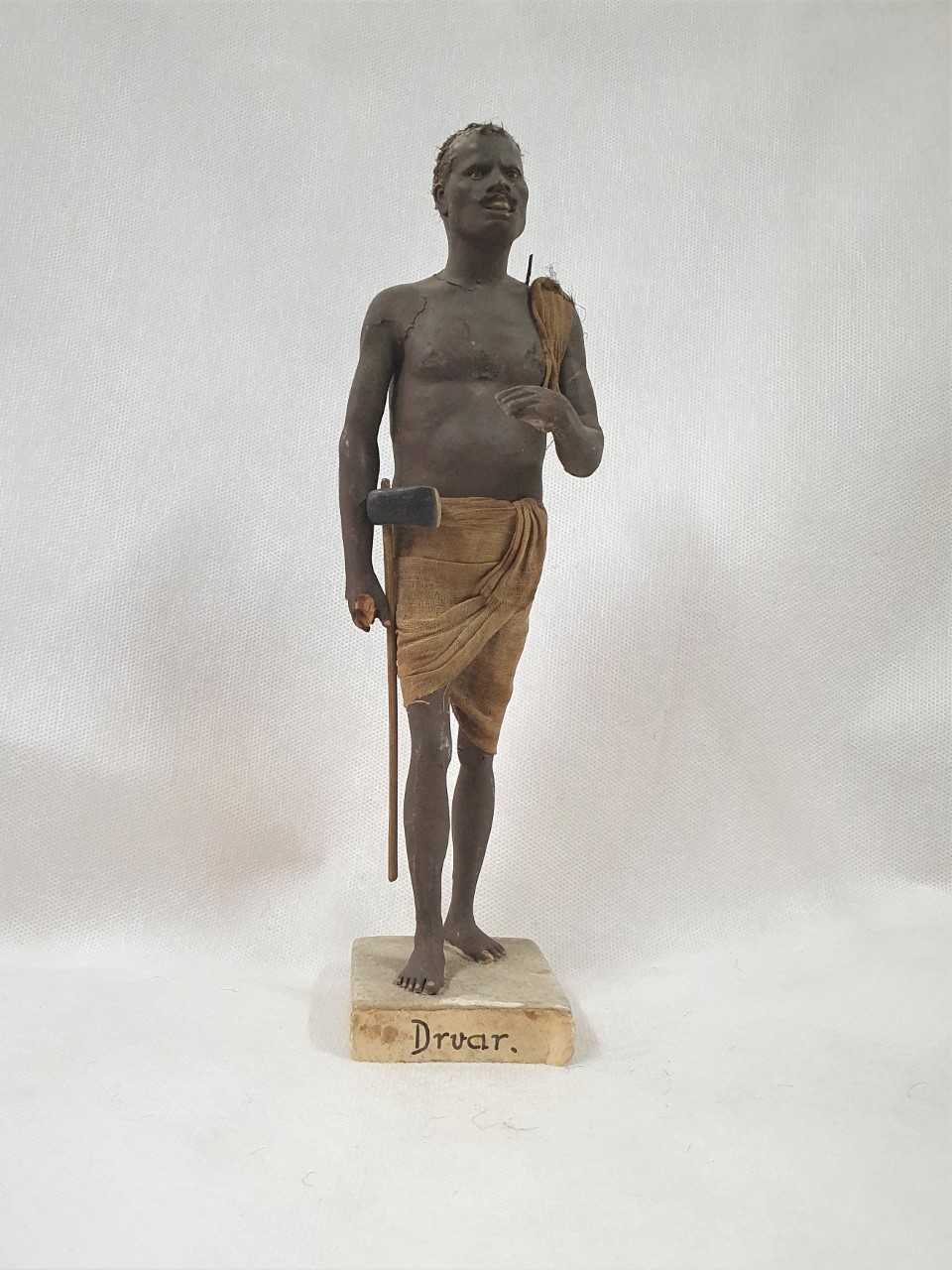

since ancient times and continues to be so even today. Another example is that

of the woodcutter, also in clay, with his axe in one hand.

The body of the snake charmer as well as the woodcutter is portrayed strong and muscular, an inevitable consequence of his labour in case of the woodcutter. Their dark, structured bodies unknowingly convey the idea of a beautiful male Indian body deserving of the same appreciation that the Indian playwrights Kalidasa and Bhasa bestow upon the male protagonists of their plays. And yet, this robustness is not a feature of every doll that comes out of this centre. In fact, most of them lack it. In the wooden dolls from the same centre (Ghurni) with the museum, one can in fact, trace a touch of caricaturization, almost colonial humour intended upon the native people. However, a few images in clay stand apart.

Perhaps the intention of these images was to fulfill colonial curiosity but in the hands of some Indian potters, the European naturalism, the style in which these images are made, became a tool to carve the rustic Indian male body, not so easily seen in the declining Indian sculptural tradition of this period.