Matters of Care Blog: The sooty tern and the swiftlet in the Pitt Rivers collection: preserving life and taking care

Locating the collections of museums within themes of care, precarious planetary futures and sharing empathy can perhaps begin with or incorporate a consideration of the ways in which animal lives, specifically birds, are preserved and navigated within Pitt Rivers Museum. From the variety of animal remains and traces within the collection, I would like to focus on three key parts of the lifecycle of birds with various cultural significances– the egg, the nest and the bird’s death and how these refract themes of preservation and conservation.

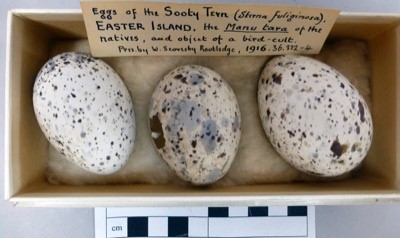

The birth and death of the Sooty Tern is one of many birds memorialised in the collection. In this case by a taxidermy adult Sooty Tern displayed with a sky scene painted behind it and a box of speckled eggs collected by William and Katherine Scoresby Routledge on an exhibition to Rapa Nui ‘Easter Island’ in 1914/15. On this exhibition, Katherine Routledge went some way towards recording the indigenous cultural significance of the Sooty Tern by collecting the names of the winners of a traditional competition amongst the Rapa Nui people to secure the first Sooty Tern egg of the season from a smaller islet (Motu Nui) to then be declared the Tangata manu (bird man). As the eggs we see in the case were collected in July, closer to the end of the egg-laying season, it is unlikely they would have disrupted this ritual practice. Yet, the ethnographic processes of measuring, describing, and mapping undertaken on the Routledge expedition including the extraction of these clearly valuable eggs, often shows the imposition of an imperial agenda through imposing specific ways of ordering. The constructed ‘knowledgeable subject’ can be seen to impose definitions and interpretations upon indigenous peoples and territories by quantifying indigenous spaces, knowledges, and cultures. The careless digging involved when excavating the statues on the island at the time, in addition to the extraction of eggs, demonstrates the need for greater care in contemporary anthropological practices which can be complimented by a deep understanding of how objects such as these displayed eggs were taken.

Though the collection of these eggs would have required great care not to break them, maintaining their fragile shape during their collection and throughout the ocean voyage, might we extend our feelings of care towards the loss of life of these Sooty Tern chicks, and see I these eggshells not only the aesthetic value of these speckled shells and their scientific value in cataloguing the Sooty Tern’s existence but the potential for life. Hence the potential for life is exhibited in both these shells and the adult, stuffed, Sooty Tern whose background hints at glimpsing the bird in its occasional island habitat, since the Sooty Tern spends most of its life at sea. With these two remnants we can wonder about concepts of preservation and how we value and conserve a species or the memory and image of it. In a time of mass extinctions remembering the species that have been driven to extinction is vital to ensuring continuing motivated efforts to preserve and respect animal life. Perhaps we can recollect when looking at these parts of the collection, as well as acknowledging their scientific and aesthetic value, the liveliness of the sooty tern which is lost along the way to the museum in traditional methods of collection and recording, and the violence implicit in their display and preservation and perhaps use these encounters as a springboard for respectful encounters with the sooty tern and other birds in our lives to respect the loss of life on display.

I would like to conclude this exploration by looking at a final item in the collection, six edible animal nests, stored in a sealed box, though now in a fragmented state, collected from the Nicobar Islands before 1884. These nests which swiftlets make from their spit have become a prized commodity, selling in China for over 500 US dollars per pound to make birds nest soup. Buildings are created and shaped to encouraging nesting swiftlets, with nests being harvested after the birds have abandoned them with care to ensure the birds return to nest again. Although this would again seem to be the commodification of bird life and labour, the careful preservation and increased creation of suitable swiftlet habitat, though not quite the caves they are used to, perhaps shows how attitudes of care, in the teamwork involved in continuing the livelihoods of both those running the nesting sites and the birds themselves, can be intertwined within current practices.

Tilburg, J.A. Van. (2004) “The Mana Expedition to Easter Island (Rapa Nui): Archaeology and Ethnology in Light of History.” In B. Dillon and M. Boxt, eds. Archaeology Without Limits: Papers in Honor of Clement W. Meighan. Lancaster, CA: Labyrinthos Press, pp.463-80.

Smith, L. T. (1999) Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London and New York: Zed Books.

n.a. (1918) “The Bird Cult of Easter Island.” Nature, 101, pp. 175–6.

Ito et al. (2020) ‘A sustainable way of agricultural livelihood: Edible bird’s nests in Indonesia,’ Social Science Research Network.