Blog post by Kanika Gupta, TAKING CARE activist in residence at Slovene Ethnographic Museum

Once upon a time …

trees fulfilled all our desires, women were unrestrained and there was no greed. The earth was covered with forests and rivers, flowers and fragrance, there was food in abundance and water for sport. Lovers met in the forest, on the bank of a river in the midst of a perfumed bower of flowers. The earth changed its colour with seasons and flowers, the water of the forested river bank was filled with Marigold, Jasmine, Parijat (an Indian flower), yellow, white, orange, the beauty of it, hard to fathom in our times. Naturally, trees were the object of worship and ancestors buried under them became spirits of the trees. Yakshi was the tree spirit, or the tree deity, a benevolent sorceress, presiding over forests and rivers.[1]

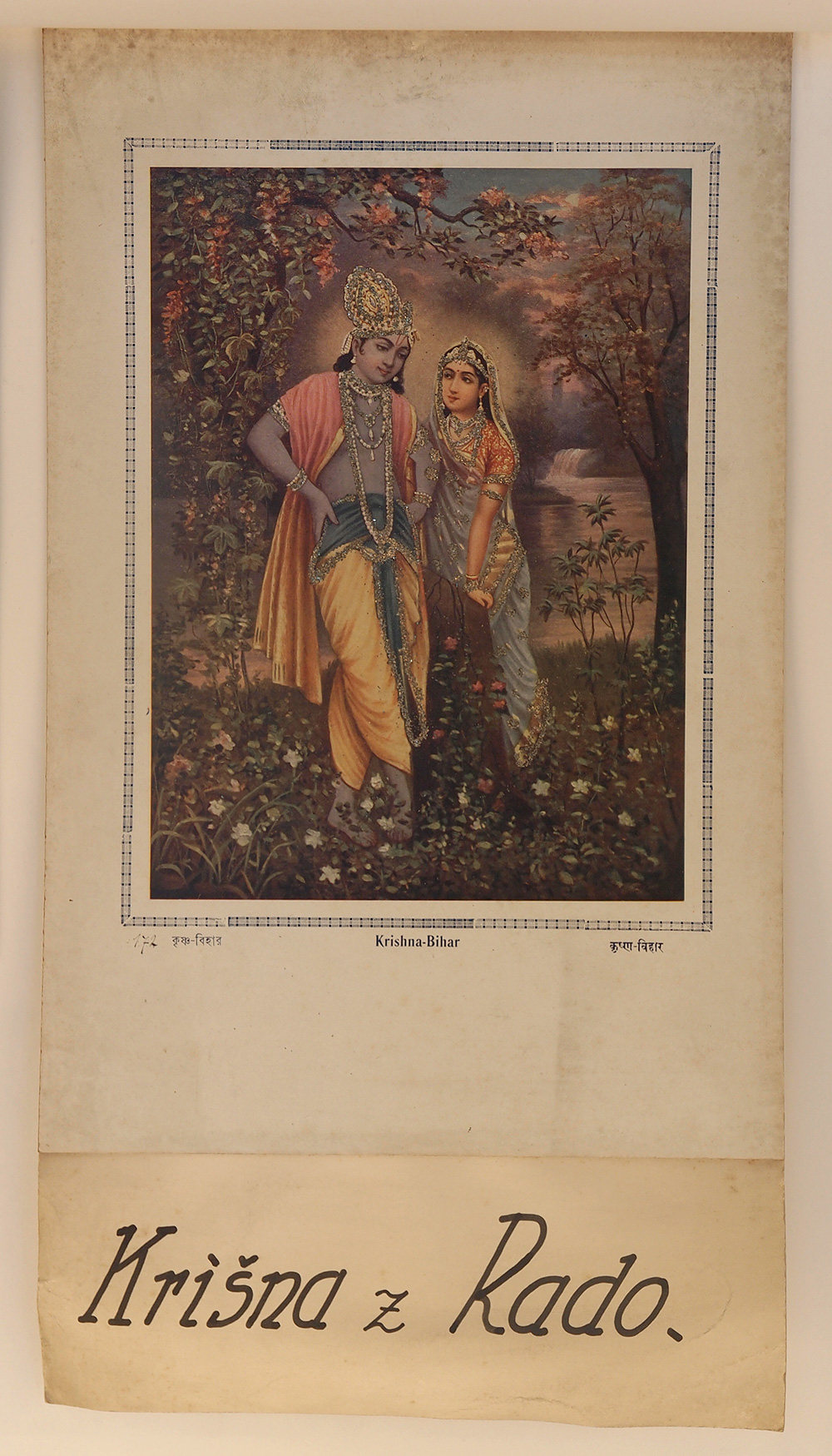

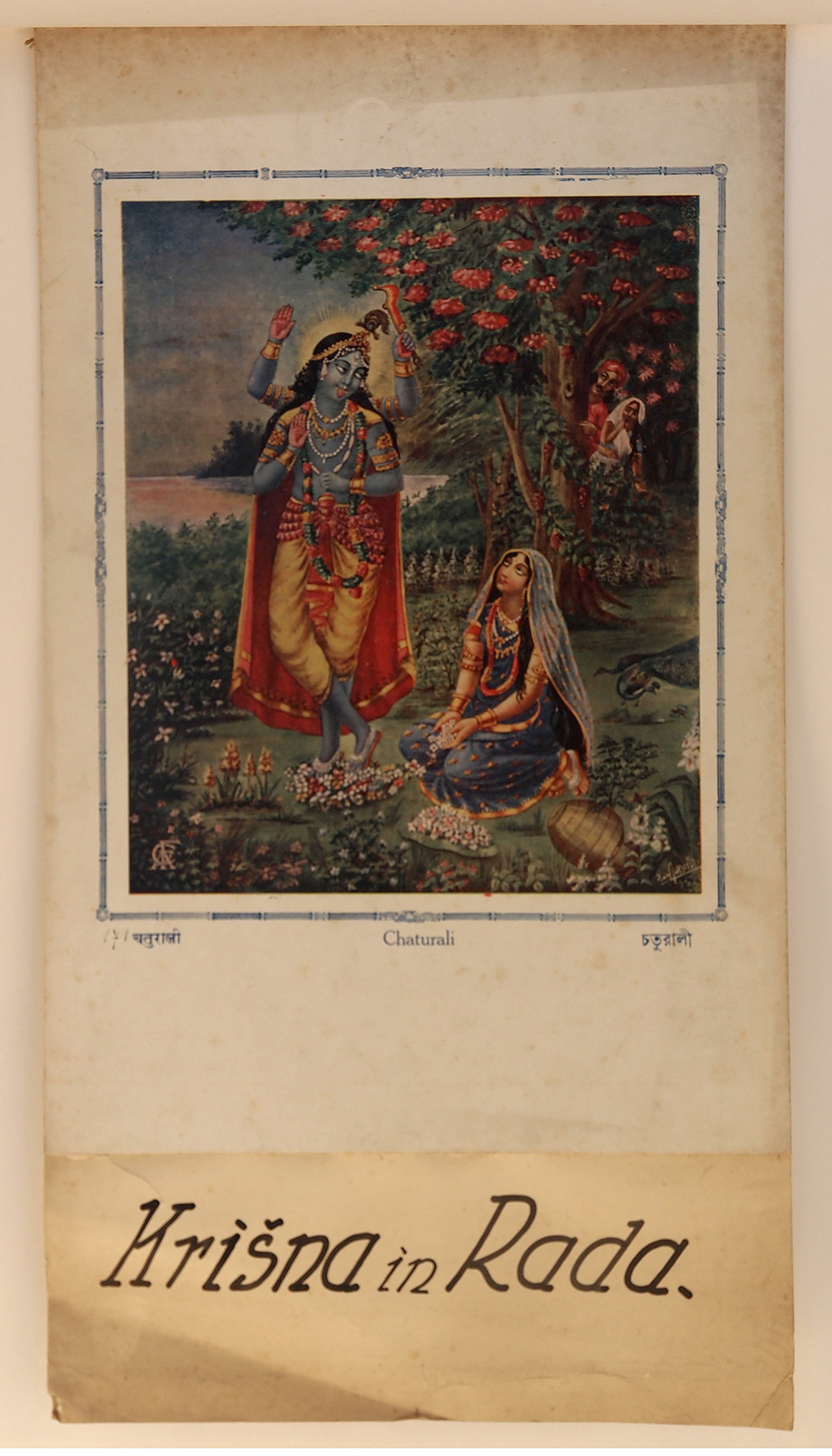

Nature manifests itself in Indian painting and sculpture from the earliest period.[2] And even while the forest cover of the Indian subcontinent kept reducing at a high rate, Indian imagery could never really give up the charms of the forests, and explored the sensuality of the forested river bank almost bordering on magic even till recent times.[3] The Indian prints in the Slovene Ethnographic Museum Ljubljana from the first half of the 20th century, though heavily dependent on the work of Indian painter and artist Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906), and the influence of camera on painting styles, retain this obsession with nature to a great extent.

The connections to nature are so deep that most literature and poetry derive its metaphors from it. The most spectacular among other examples is the description of Basant ritu, that is, spring season when trees are full of fruits and flowers grow in abundance, when swings are hung on the strong old branches of trees and lovers decorate themselves with nature's bounty. An entire genre of poetry in India called Barahmasa (of twelve months) describes changes in seasons and their splendour along with the protagonists moods. This poetry, like many others, was then translated into paintings. Thus the Indian painters drew from not just the nature they were surrounded with, but also from the poetry they inherited which was overwhelmed with enchantments of the forest.

The performance The Cursed land of Lustful Women draws inspiration from all these references. It centres around everyday pleasures of life lived in nature, in peace with it, in its enchantments. It dwells upon the aesthetics of Indian imagery built around nature. It touches upon the pose of the Indus Valley Bronze dancing girl, Canda yakho and Sudasana yakho, tree deities of Bharhut sculpture and Ravi Varma pose of Shakuntala, who stands in contrapposto picking a thorn in her foot as an excuse to take a peep at her lover among other Indian references.

This small performance narrates a folk story which comes from the times when a social and environmental transition was taking place. Man began to strive for more of everything, more resources, more power and greed, and more and more greed.

Though loaded with meaning and symbolism, it is simple in its narrative, a characteristic feature of old myths. The performer, trained in the Indian dance tradition Kathak, derives gestures and movements from that dance form to tell these stories, taking liberty with it and yet going back to the roots of Kathak as a performing arts form in which the primary agenda was to tell a story. Like most other Indian dance forms, Kathak is loaded with references to nature, trees, flowers, river banks and forests. The river bank in the forest is the inevitable rendezvous for lovers in poetry, literature, painting, music and dancing traditions alike. Each of these constantly refer to the other.

The performance suggests sentiments without too many words and connects everyday life with nature. The performer attempts to focus on sounds of nature, the wind, trees, the insects, the firefly, on the verge of extinction in India and the gentle hum of night, and takes these as music instead of recorded sound. The performance is full of movements done in silence, redolent of sentiment, the juice of aesthetic pleasure.

Who is she? the narrator? the sutradhara (director) of Indian theatre from Natyashastra, the ancient Indian theatre book? Is she the princess in the story? Or is she the tree ... perhaps she was ...

[1] References to folk stories are found in Buddhist Jataka stories, Jain text Vasudevahimdi, and also Mahabharata.

[2] Bharhut sculpture dated to 2nd century BC. Also nature is significantly portrayed in the Indian painting tradition, for instance Barahmasa paintings.

[3] In Company school of art as well as the prints in the Slovene Ethnographic Museum collection.