Over the past decade or so, museums have become deeply involved in telling stories of migration, displacement and refuge. The Pitt Rivers is among them, with its 2019 exhibition Lande: The Calais ‘Jungle’ and Beyond – I would like to focus on the only object which was accessioned by the museum after the exhibit ended.

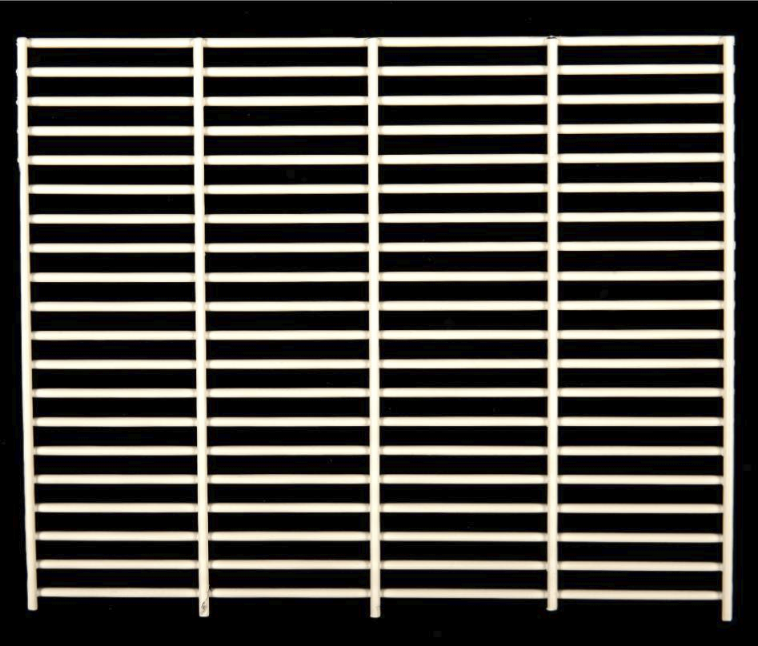

This metal fence once stood as a border, preventing the migrants at Calais from crossing into the UK. It was acquired in Ashford, Kent. It is less than half a meter in length and width, and is only 5 mm thick. In the Pitt Rivers Objects Database, it has been classified as a weapon.

This was one of the many objects on display in Lande, and perhaps one of the most striking. But most importantly, to me at least, it brought attention to the way in which narratives of refuge are constructed and represented, both by traditional and popular media, but also by museums. Representations of refugees and migrants can often bleed into an over-emphasis on tragedy and ‘crisis’, frequently painting them as one-dimensional caricatures of misfortune. But as much attention is paid to the stories of migrants and refugees, there is often a reluctance to address why these stories are always framed via a lens of emergency and tragedy. This object stands out to me as an outlier – a stark reminder that the abysmal treatment of refugees is a deliberate and intentional choice that is made by national and international bodies. A choice that is often glossed over or mentioned in passing in such exhibits.

What is often never mentioned at all are the legacies of colonialism and Empire that are seeped into the very bones of not only refugee camps, but also in the conflicts that led to the establishment of such spaces. It is deeply ironic that where the Calais camp once stood, a sanctuary is now being erected to house migrant birds. Using the language of conservation to justify pushing out those seeking refuge is, unfortunately, nothing new – this language is, after all, another way in which the legacy of colonialism performs violence on black and brown bodies. But it is something we should all be a wary of as we discuss themes of planetary precarity and taking care.

Gouriévidis, L. ed., 2014. Museums and migration: History, memory and politics. Routledge.

Hicks, D. and Mallet, S., 2019. Lande: The Calais' Jungle'and Beyond. Policy Press.