Interview with Narelle Jubelin, TAKING CARE artist-in-residence at the Museu Etnològic i de Cultures del Món (Barcelona)

Narelle Jubelin (b. Sydney, 1960) has been engaged in a residency at the Museu Etnològic i de Cultures del Món (Barcelona) since mid-September 2020. Her personal look at the museum’s Tiwi collections will allow her to create a work of art and possibly an exhibition, with which to establish a complementary narrative from the one established by the museum. In addition, her enquiry is enriched by the dialogue she is establishing with different Australian artists and experts, including Tiwi artists, so that the voice of the communities of origin is heard and that they have a stake in her narrative.

First Nation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised

that this conversation contains mention of deceased persons.

Salvador García Arnillas (Curator of the Museu Etnològic I de Cultures del Món): First of all, I want to thank you for your commitment to our Museum by going ahead with this residency in the midst of a pandemic. How are you experiencing the situation in Barcelona?

Narelle Jubelin: To be frank, it took ages to decide whether to accept the invitation given that I would naturally recommend artists from communities represented in the collections to take up the opportunity for such close contact with the material holdings. The initial invitation came, then Covid struck, and as you know we were uncertain until the very last moment if travel between Madrid, where I am based, and Barcelona would be possible. Travel from Australia or for Indigenous artists that may have already been working outside of Australia, in Europe, would also not have been possible. We have subsequently been working against a kind of second wave clock not knowing if an artist in residency, that insinuates displacement, would be possible. So, on hitting the road running our emphasis has been in accessing as much of the Australian collection in the flesh as possible before things become even worse... And in fact, as we edit this interview, we have just one day left to be on site in the Museu Etnològic I de Cultures del Món before Catalunya returns to confinement, and we all regress to work long-distance from home.

SGA: Throughout your career you have carried out some residencies / collaborations in museums, art galleries and universities. As a contemporary artist, is there any difference in working in an ethnological and world culture museum?

NJ: It is very different working in a museum that has a collection. This is only the second time I’ve been invited to do so… the first was at the National Gallery of Victoria in the early 1990s and was more to build onto or expand a work of mine already in their collection by incorporating objects from their permanent collection. As you intimate in your question Salvador, an ethnographic museum is another beast. Museums are always contested spaces and when there is a history of mounting collections in order to represent ‘world’ cultures we know by experience that that is grounded in Eurocentric assumptions. Both by definition and necessity, such museums are more contested than most.

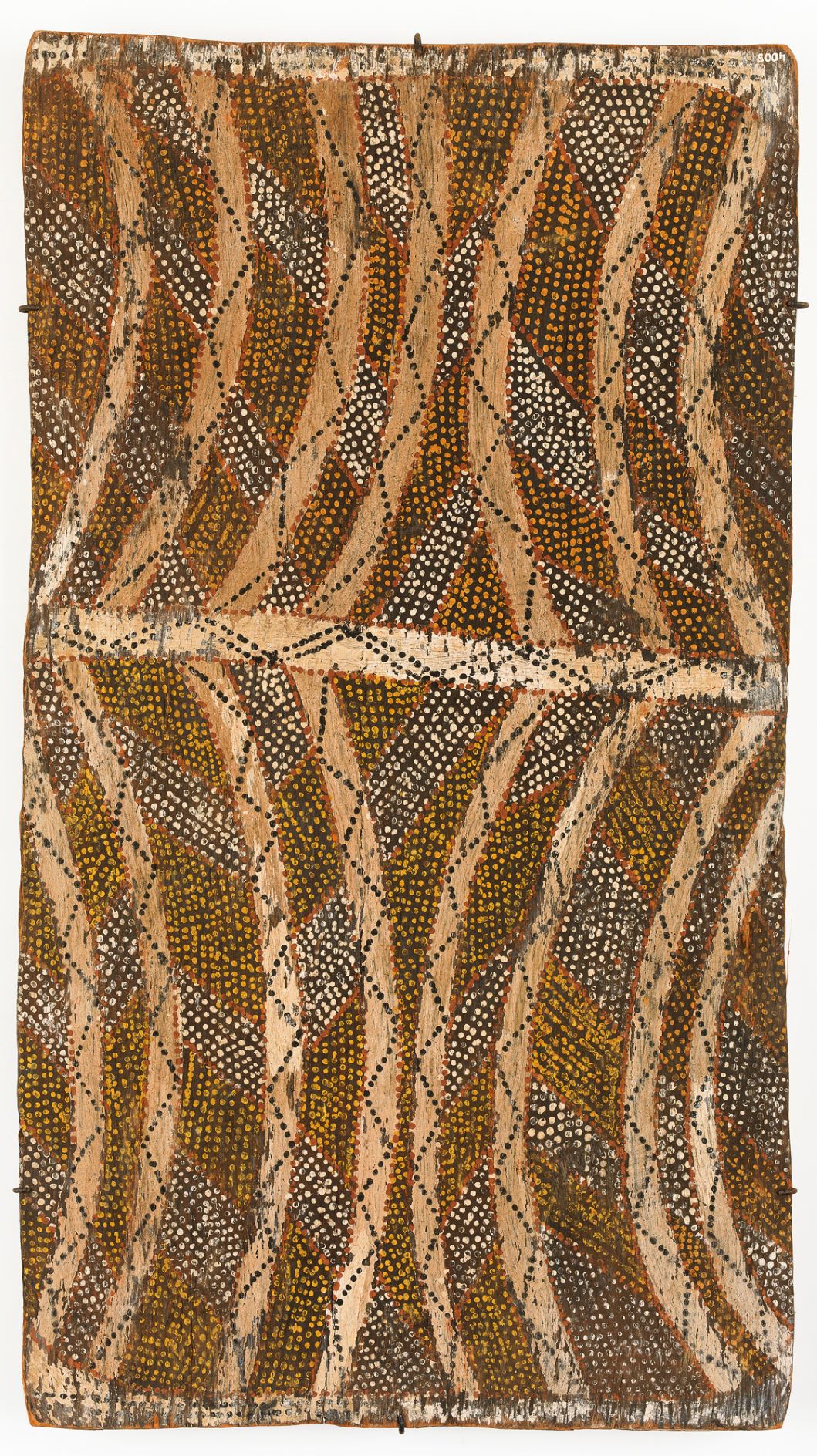

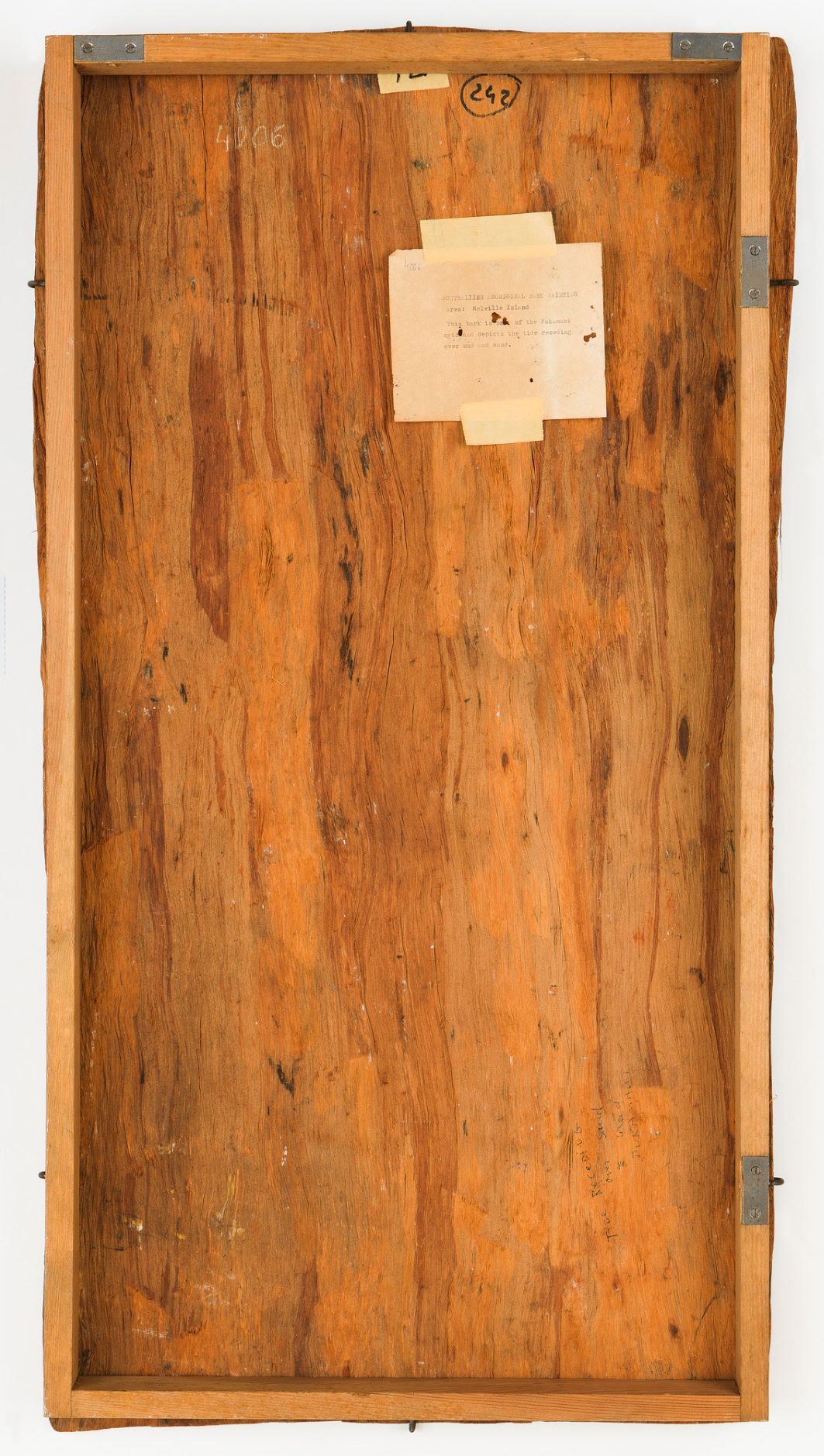

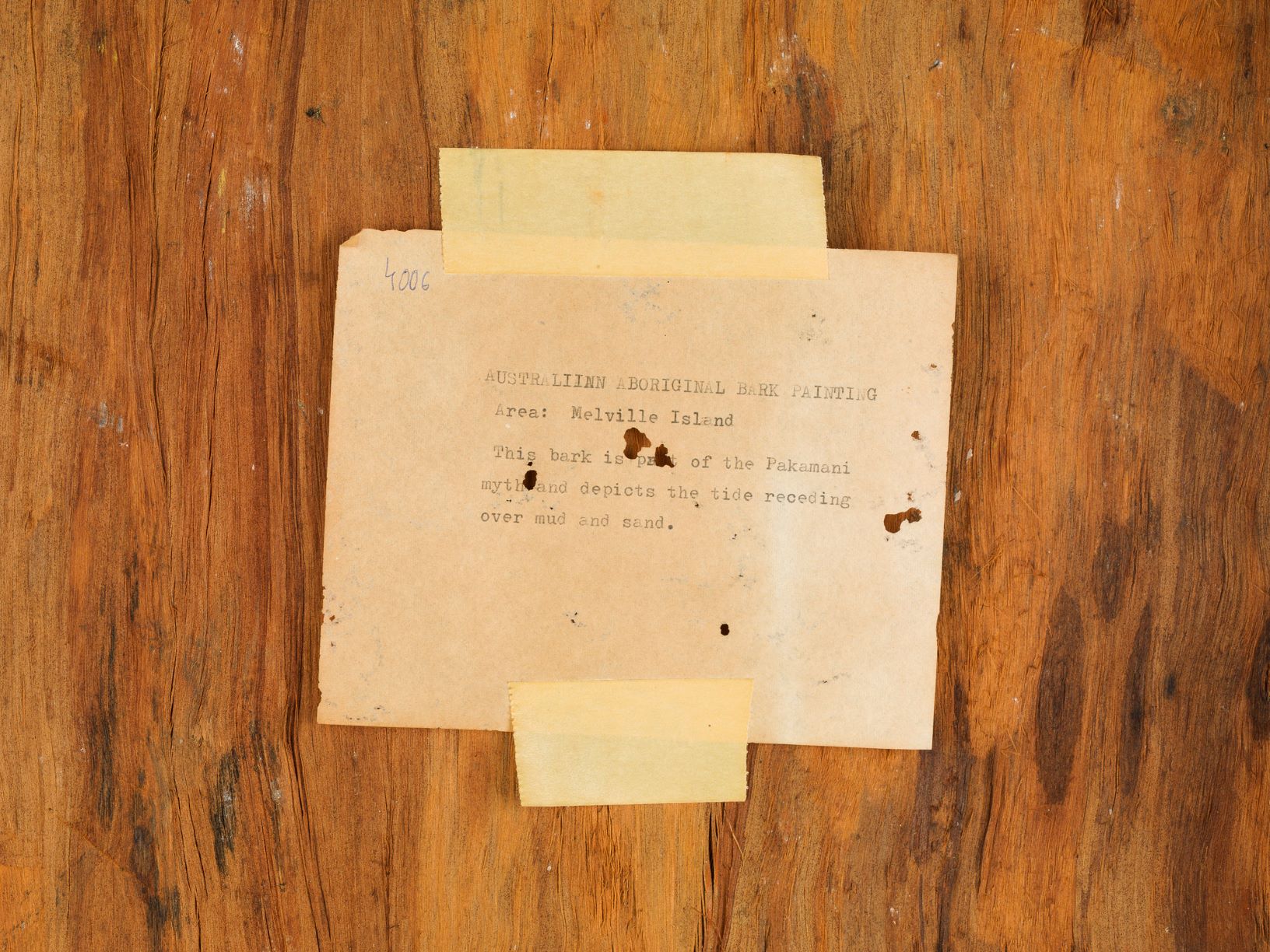

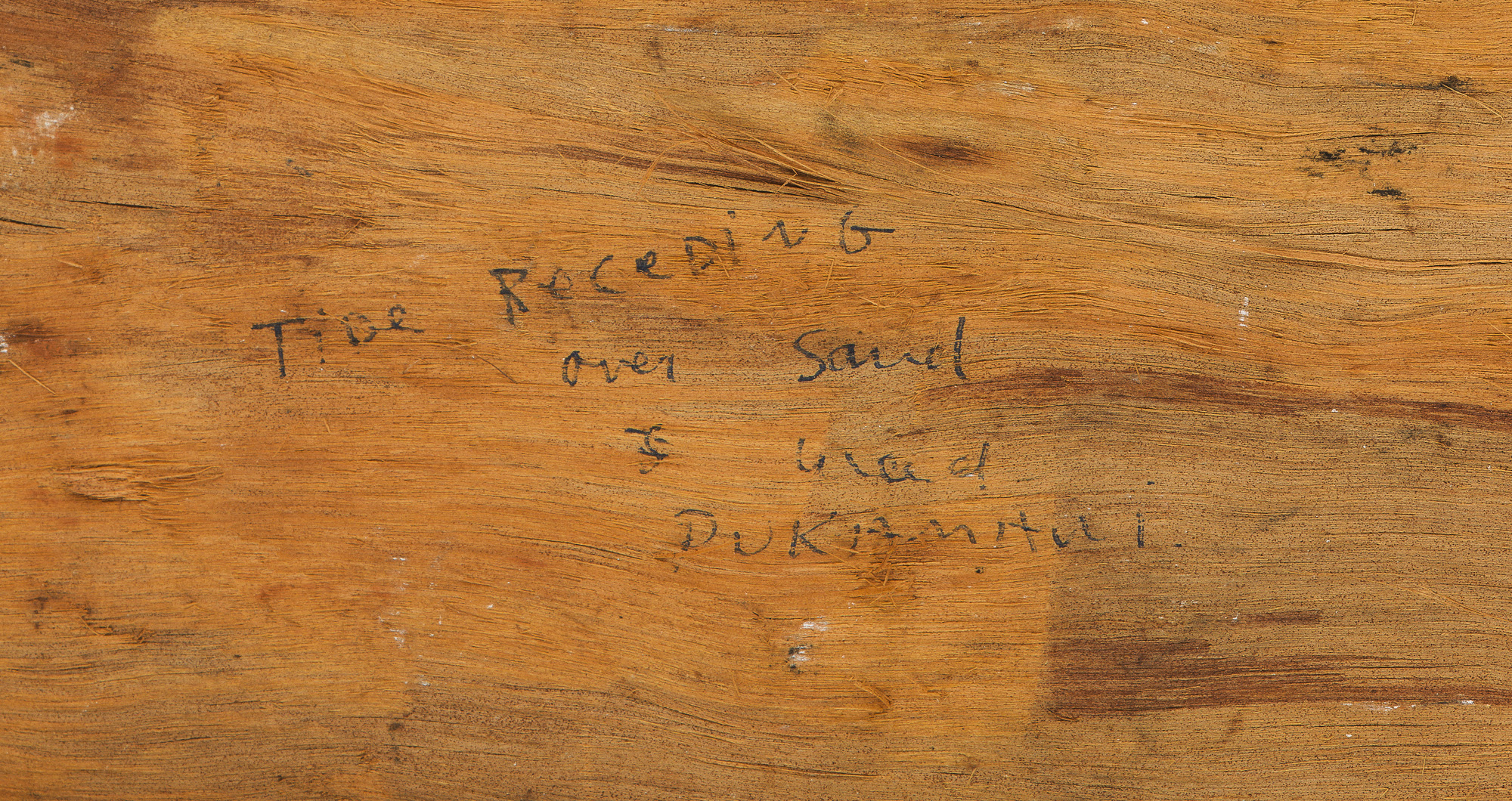

Throughout the residency the Curators and I have been reaching out to Tiwi Island traditional custodians—one of the source communities—and hopefully they are able to think of me as a research assistant. We seek conversations with the Tiwi Island Art Centres that have grass roots connections with senior people so that the project can be established on an artist to artist basis. We are preparing an inventory of the little-known collection of Tiwi Islands cultural materials, that includes photographs and some video. There are bark paintings in particular purchased in the late 1960s early 70s that the community may be very interested to see.

I envision that, from the Tiwi perspective, it might be a bit like reencountering a living archive. One of our artist interlocutors, Diana Wood Conroy, like many feminists of her/our generation who went into the Tiwi community to work, said that senior artist leader Bede Tungutalum, who founded Tiwi Designs Art Centre in 1968, calls bark “skin”. These are small but important revelations: we will be led by them.

The renowned senior artist Pedro Wonaeamirri from Jilamara Arts, established in 1989 [i], has also agreed to guide us, making bridges where appropriate with other people there on their island grounds.

SGA: As a non-Aboriginal Australian artist, what is your method of engaging with the Aboriginal culture of the Tiwi?

NJ: Short answer is dialogue. In the benchmark 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart[ii] Indigenous Australians stated that the quest for a “Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.” Hence as a non-indigenous person, only a few years ago, we were clearly invited to participate, now there is a very real sense that we are compelled to participate and that this is a process that is well underway in Australian culture(s). We will be led by First Nation peoples in the redefinition of our national debates.

As one example, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations’ community response to the pandemic has been impeccable: there have been no community outbreaks of the disease thanks to public health policies implemented from within the communities.

Moments of material and personal contact with any culture are tentative and generally born out of small details. After decades of trying to get my head around Spanish culture(s), needless to say where complex and contentious national debates rule. In 2012 I travelled with my Madrileñian partner Marcos Corrales Lantero and our son Nelson to the Australian Northern Territory. In a sense it was their turn to be culturally marooned. It was only when we returned to Madrid and were backing up drives and pooling photographs or video footage we’d shot that I saw a small fragment of footage that Marcos had filmed with senior Tiwi artist, the late, great, Jean Baptiste Apuatimi welcoming us, part of their audience, to the Annual Tiwi Art Exhibition held in Darwin.

I would not have thought to film her Welcome to Country. Marcos did and at the end—again I reiterate of this tiny video—he also caught himself responding with a kind of whoooop of appreciation to her dance. When I heard his voice, more akin to his response to flamenco than to an Elder acknowledging local ancestors with her fellow Tiwi artists being away from their islands and on the mainland, and to the Elders past, present and future of her Tiwi communities that I recognised the complexities of what Marcos had captured. As ever the subtle nuances of cultural difference and interpretation are at the roots of this residency.

While we are accessing the collections in the Museu Etnològic I de Cultures del Món and the Fundación Folch I am also starting to hone in on two tungas or imawalini (painted bark baskets), part of the heart of Tiwi Pukumani (burial ceremonies)[iii] that fed into the late artworks of Jean Baptiste Apuatimi. I am yet to ask if she was also consulting museum collections but she was clearly acknowledging, reinforcing and reiterating the continuities of her local traditions. And here this conversation is like a working document as I’m just beginning this line of enquiry. I know though that I am keen to continue marking the cultural importance of Apuatimi’s practice... Notwithstanding, there are protocols to observe and I still need to consult.

SGA: Now that you are aware of this collection of Tiwi objects we hold on the other side of the world, what are you thinking to do with it?

NJ: The short answer again is: dialogue. I think I will somehow return to Marcos’s footage as I’d asked permission to exhibit it with video footage of another senior artist also videoed in 2012 on a Mobile Residency working in Timor Leste. It is a short sequence with Domingas Soares and her family outside her house, weaving a traditional Timorese textile tais. It plays in a loop intercut with Jean dancing in the clothes made of the cloth she had silk screen printed with her Jilamara (design).

Sadly, during that exhibition Jean Baptise Apuatimi passed away so I needed to contact Tiwi Designs, with whom she had worked for many years, to ask what I should do. Should I withdraw the video piece from exhibition? In a flurry of early morning emails, her family was consulted, and the message came back to me that the family was happy for her name to be used and for that video to remain screening for the duration of the exhibition.

That morning, as I’d read her obituary, forwarded to me by Jo Holder who had written for the catalogue of the exhibition currently in train; and as I awaited Jean’s daughter Maria Josette Orsto, also of Tiwi Designs, to get back to me from her family, the first snow of 2013 fell in Madrid. I filmed a minute of that snowfall. As it fell, dots formed cross-hatches (so reminiscent of her mother’s silk screen cloth), backlit against the sky. I sent the memorial video through to Maria Josette. Since then I have filmed the first minute of the first snowfall each year—if there is one where I am— for that old woman... whom they called Queen.

During my stay here in Barcelona we’ve been able to record at unusually close proximity some of the Tiwi cultural material so as to send documentation back to the Art Centres. Close looking is a privilege that I don’t underestimate and, as we spoke of earlier, at this moment in time actual physical movement is restricted. However, within this residency I have been given unimpeded access to the collection. Slow camera movement stands in for that access while the advent of modern “free messaging” means that we can use Skype, WhatsApp or whatever to share image banks, entering into dialogues in ways that were unimaginable only a very few years ago. We need to transit those vast distances, for now, in different ways. And thinking aloud, in this hemisphere, the tenuous snow season coming cannot better hint at the massive conceptual distance from the Mediterranean to where the Arafura Sea meets the Timor Sea.

SGA: Plying thread is at the heart of your work and since the beginning of this project, I have witnessed how you have been “weaving” a relationship between the objects in our collection, the Australian artists and experts who have accompanied you with their friendship for decades, and, of course, with other Tiwi materials, images and voices from the communities themselves. How can we weave a valuable, lasting relationship between a European museum and the communities of origin that are thousands of miles apart?

NJ: Good question. Artists build communities. I could not have accepted this invitation without the background of a carefully constructed bank of friends who are practitioners as sounding boards who are generously there for me, for us. Not only Australians: this morning you handed me the exhibition catalogue from a rigorously researched exhibition ‘Indigenous Australia Enduring Civilisation’ at the British Museum that in its own way was a significant—one could even say rare—collaboration between British and Australian institutions, researchers and communities that provoked quite a fall out in Australia with some source communities “wanting their stuff back”. So again, the short blunt end of the stick answer has to be: by reaching out into those communities and seeking dialogue. I still don’t use the word “exchange” as we all remain conscious that the exchange is never equal.

SGA: The residency is part of the TAKING CARE project in which our museum is participating with twelve other ethnological and world culture museums. The project reflects on museums as spaces of care for people / communities, collections and the environment, in an increasingly precarious world. The concepts of “shared authority” and “community participation” have a special relevance in the museological debates of recent years. Also, in Australia the concept of “voice” in the relationships established with Aboriginal communities is fundamental. What role do these concepts play in the artistic proposal that you are now developing?

NJ: The modes of practice that you cite in your question are established with care and over time wherever and whenever they are sought as modes of practice and not simply debated. As progressive museums there is a need to be prepared to ask the difficult questions. In the first week of this residency there was a series of TAKING CARE web meetings organised by the Research Center for Material Culture (Leiden). Clearly those of you committed to working in museums associated with this venture are prepared to do just that. Even given that the questions posed in the encounters were taxing and within the participating institutions there will inevitably be resistance to the challenges that those said questions pose as they challenge the very roots of collecting institutions. In several moments of the presentations we watched your museum colleagues openly squirm in the presence of their expanded, if virtual, public.

In a very real sense within this residency I just hit and run but what I’m experiencing here, the impact of this short stay in this museum, does form part of the ongoing evolution of what ethnographic and world culture museums can be. I am conscious of, and almost by default, participating in, a kind of self-examination, a self-conscious critique, not only about the end of museological empires but about the potentials of building and sustaining community through astute interlocutors from within the museum fields and far beyond.

The dialogues that you are actively engaged in demonstrate that the participating institutions have increased since last year, and more importantly that this growing interrogation is developed as a long term proposition where the discussions will be ongoing and, dare I say, escalating given the precarious global situations that you hinted at earlier. These commitments are akin to the kind of critique that artists know as practitioners where we are actually never sure about what we are doing but we draw on the always generous, rich collective experience that surrounds us. The impetus for “voice” that you mention is only the first requisite of a Makarrata that pertains to Voice_Treaty_Truth and so with tides shifting, time will tell.

Barcelona, November 2020.

i Jilamara Arts and Crafts Association is a Tiwi-owned art centre at Milikapiti on Melville Island. Artists at the centre have made a significant contribution to contemporary Indigenous art in Australia since the association was established in 1989.

ii https://www.sbs.com.au/language/english/podcast/the-uluru-statement-from-the-heart-in-your-language [Accessed November 17, 2020]

iii https://tiwilandcouncil.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=page&p=249&l=2&id=60&smid=121 [Accessed November 17, 2020]