Behind the Scenes: Working with the Ugandan Barkcloth Collection at the MAA

The Stores Move project at the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (MAA) have been busy documenting, photographing and packing over 250,000 objects from 162 countries ready for transfer to the new Centre for Material Culture (CMC).

Earlier this year, as part of on-going project work, we prepared a collection of 38 lengths of Ugandan barkcloth at MAA. With no photos on the database, we had little idea what was in store. From unrolling four-meter lengths of barkcloth to unsolved museum mysteries, here’s our journey from storage retrieval to collection engagement at the CMC.

What is barkcloth and how is it made?

Barkcloth is a type of non-woven cloth made from the inner bark of trees. It is produced along a tropical ’barkcloth belt’, including but not limited to the Pacific Islands, India, South and Central America, the Caribbean, West, Central and East Africa, and is used for multiple purposes such as clothing, masks, and mats.[1] Reddish-brown in appearance, Ugandan barkcloth is made from the bark of the mutuba tree, Ficus natalensis, which is repeatedly beaten with wooden grooved mallets or beaters, to create a soft, thin cloth.[2]

Some of the first objects we encountered that were related to the Ugandan barkcloths were the beaters, which you can see below. The grooves along the heads of these beaters gave us a good insight into the way the cloth was produced.

Documenting the Details

The next step was retrieving the barkcloth itself from the stores. The Ugandan barkcloths at MAA vary dramatically in size, with the smallest at 53cm x 16cm and the largest 459cm x 248cm. Due to their large size, many of the barkcloths are stored rolled onto acid-free cardboard tubes and hung from poles. This protective technique avoids folding them and prevents creating new creases which can lead to permanent damage. To fully unroll the barkcloths, and to allow us to examine and document them, we moved from our desks to the floor, which had been prepared with conservation grade coverings to protect the objects.

Upon unrolling, we noticed that in many instances the beater marks are still visible upon the barkcloth, sometimes forming intricate patterns.

Our observational skills were useful as contextual information for the Ugandan barkcloth collection survives unevenly in the museum’s records, limiting what we know about their past. Between the late-19th century and mid-20th century, the collection at MAA slowly grew as a result of bequeathed and donated cloth from multiple sources.

Looking at the object records, the barkcloth collection at MAA is predominantly associated with the Ganda or Baganda people, whose homeland is the kingdom of Buganda, from which the country of Uganda gets its name. A key source of contemporary information to MAA can be found from the prolific donor, Reverend John Roscoe. An English missionary and ethnographer in Uganda during the late-19th and early-20th century, influenced by Royal Anthropological Institute practice from the period, Roscoe captured his experience living with the Ganda people on object labels and in his 1911 book, ‘The Baganda’.[3]

Roscoe writes that barkcloth is a multi-purpose material, with strong cultural significance. Examples of use include clothing, wall divisions and bedding.[4] This possibly relates to examples in MAA off-site storage which were donated by Roscoe.

Up close examinations also revealed fascinating contemporary repairs in the barkcloth. These were delicate yet strong and almost invisible from the front, with the reverse revealing precise and tight stitching. Roscoe describes the repair process as follows

The men were experts at filling in places where there were flaws in the bark; they cut out the bad pieces, and fitted in other pieces, and stitched them so neatly with plantain fibre that they did not show.[5]

Museum histories and mysteries

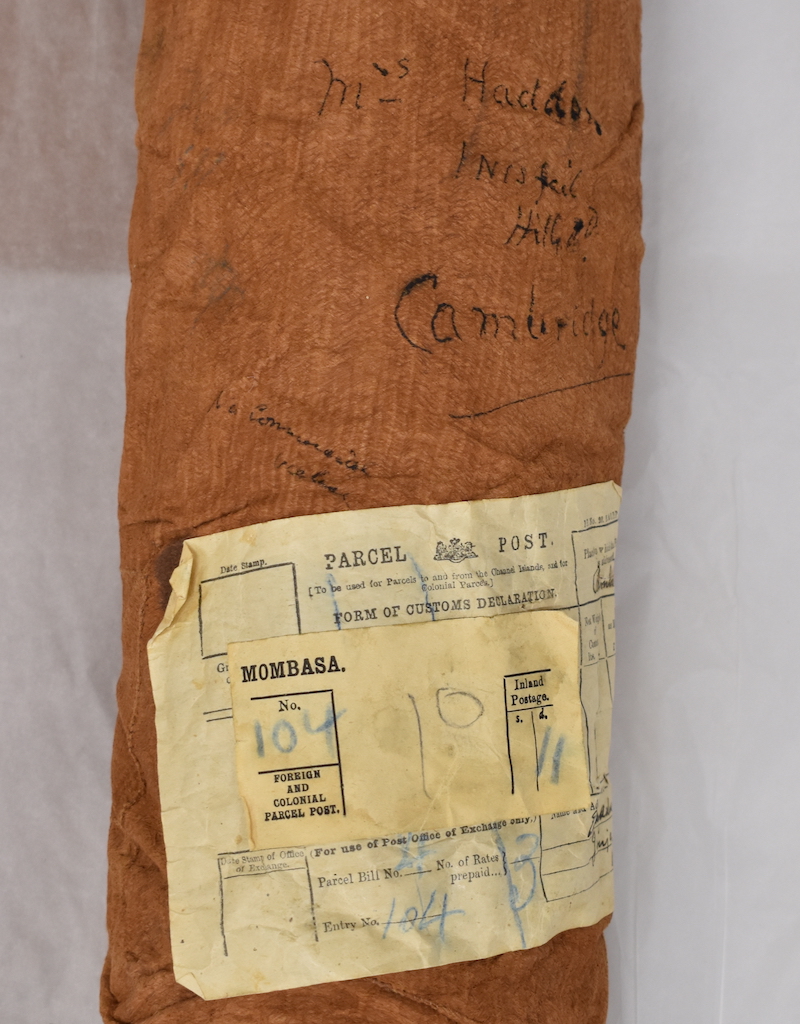

We were also able to spot clues about how the barkcloth may have arrived at the museum and get a glimpse into their lives post collection.

Several lengths had a price written on the reverse, and even Cambridge postal addresses and customs declaration forms attached directly onto the cloth (see Z 19414 C and Z 19414 D on the MAA online catalogue). Was the barkcloth marked for its own transportation, or was it used as a wrapping for other objects? Were they even intended to be a museum objects?

Examination of the objects below also revealed that they had been hemmed along one edge on an unknown date. Could this have been a material change after the cloth entered the museum, possibly for use as a display backdrop?

Overall, 14 of the 38 Uganda barkcloths at MAA are decorated with black, hand-painted designs. One group of decorated barkcloths were particularly intriguing. Accessioned into the museum together (accession numbers: 1924.951 A-Q), similarities in design motif and cutting style along the edges led us to wonder, were some of these pieces once part of a much larger barkcloth? Looking at this image, what do you think? Why would they have been cut up?

Packing the Barkcloth

After updating the online database with our findings, we set about re-packing them for transport to the CMC. As mentioned earlier, one of the best ways to pack large textiles is rolled onto tubes to prevent adding creases and damaging the cloth. Another added benefit is that this also maintains historic folds which hold the potential to show how the cloth may have been worn or used. As you can imagine, keeping a balance between ensure neat tight rolls and being cautious of the delicate cloths was tricky work! We rolled the cloth between sheets of acid-free tissue paper onto the tube, which we then wrapped in a waterproof and dustproof Tyvek layer and suspended upon a pole. As a result, we regularly had to unroll and re-roll so as to ensure that pressure was just right. Check out the time lapse below of us going through this process.

A timelapse video of Emily and Jane rolling barkcloth. Video by Sam Daisley.

Sharing our project journey

After weeks of documentation and packing, in April 2022 we were invited to contribute toward a hands-on session using collections at MAA as part of the Creative Europe funded TAKING CARE Project. The project brings together museum professionals from 13 institutions across Europe. We leapt to the chance to present a selection of barkcloth. It was wonderful to present and discuss our experience working with the barkcloth with an audience of receptive museum and heritage professionals.

What is next for the Uganda collections at MAA?

An exciting project, Repositioning the Uganda Museum, is working towards the return of historic artefacts to the Uganda Museum in Kampala. We hope our documentation of the Ugandan barkcloth collection has helped to make their records more visible and accessible in preparation for these important developments.

Please keep an eye out for other Stores Move blogs and CMC open days as we continue our project journey, relocating archaeology and anthropology collections from MAA off-site storage to the new CMC.

Sources of Information:

[1] National Museums Scotland. Understanding barkcloth at National Museums Scotland. [Accessed: 19/08/2022].

[2] Worden, Sarah (2016). Tradition and Transition: The changing fortunes of barkcloth in Uganda. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1012. Pp.596-7.

[3] Roscoe, J. (1911). The Baganda; An Account of their Native Beliefs and Customs. London: MacMillan and Co. p. 493.

[4] Roscoe, J. (1911). The Baganda; An Account of their Native Beliefs and Customs. London: MacMillan and Co., pp. 5, 8, 107, 402-3, 406, 442.

[5] Roscoe, J. (1911). The Baganda; An Account of their Native Beliefs and Customs. London: MacMillan and Co. p.406.